Continuity and Change Over Time Apush Jefferson and Jackson

Knowing how to answer AP® US History Free Response Questions is an art. If you're looking for the best tips and tricks for writing APUSH FRQs, you've come to the right place.

In this article, we'll review a five-step strategy to writing top-mark AP® US History free response answers, mistakes students often make on the APUSH FRQs, as well as go over a compiled set of tips and test taking tricks for you to incorporate into your responses.

Keep reading to get the scoop on what you need to know when it comes to maximizing your limited AP® US History exam review time.

5 Steps on How to Write Effective AP® US History Free Responses

Here, we'll review a five-step strategy for you to start writing AP® US History free response answers that will score you maximum possible points.

1. Master the three different rubrics for the AP® US History SAQ, DBQ, and LEQ.

The biggest mistake a student can make when it comes to preparing for AP® US History is never truly understanding how they're going to be graded. This leads to scattered responses that do not provide the specificity that translates to points on the exam.

To solve this, you'll want to go to the College Board's AP® Central website and navigate to the previously released exams for APUSH:

Here is the link for AP® US History past released exams

Open up the scoring guidelines PDF. These guidelines outline how points were distributed on that particular year's exams.

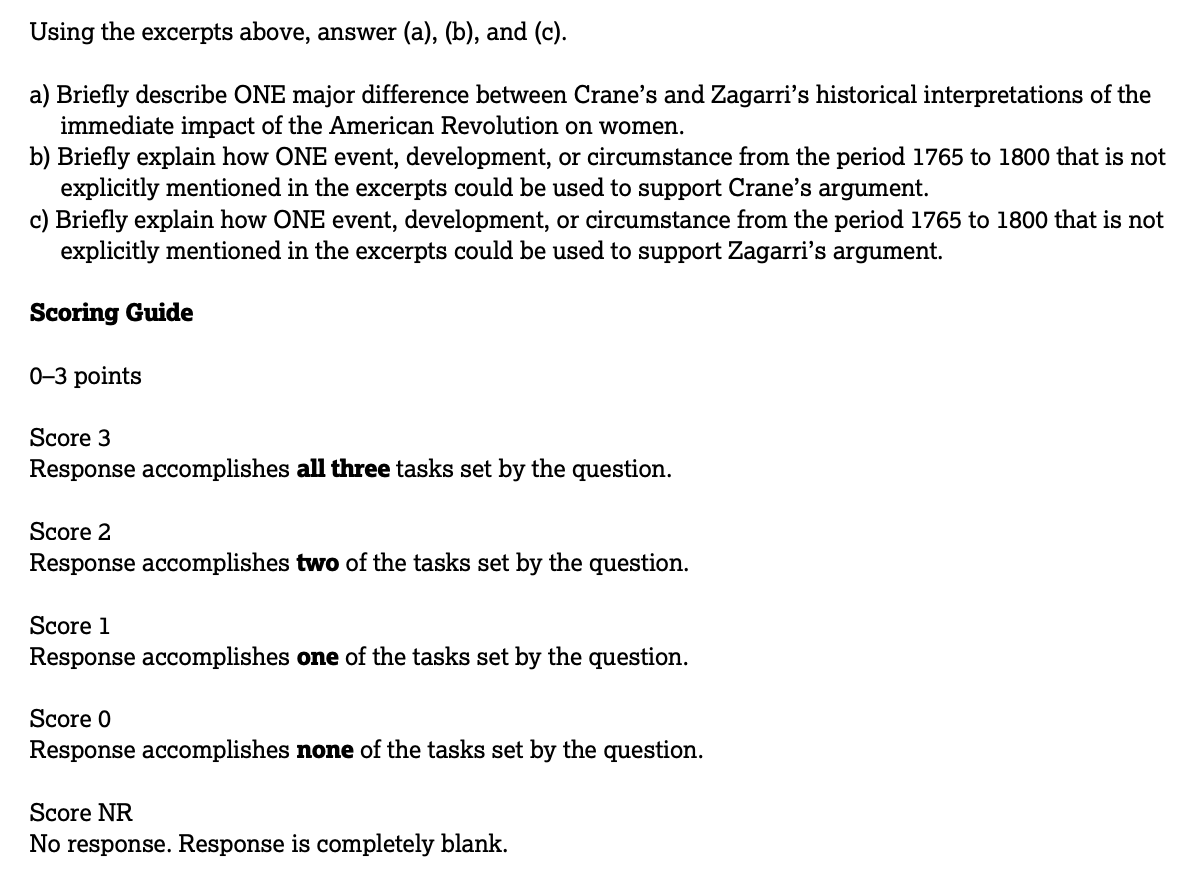

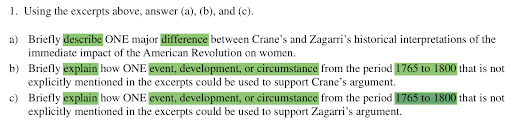

Here's a screenshot from the first question of the 2019 released exam:

Source: College Board

From the above, you'd see that the first SAQ was worth three points, and each point was awarded for successfully completing the task asked within the question. After reviewing a few of these questions, you'd start to notice the level of specificity the graders require in order to earn points. For example here you can see that in order to adequately describe the differences between the two sources' historical interpretations, students had to explicitly state the positions of both authors.

Source: College Board

As you familiarize yourself with each type of question, you'll start to notice the College Board always uses a predictable set of directive words in their questions. We'll cover that later in this post.

For now, be sure to review the last two years worth of released exam scoring guidelines so you can begin to understand how SAQs, DBQs, and LEQs are scored.

2. Underline or circle every bolded and capitalized word in the question prompt.

Now that we know how points are broadly distributed, we need to have a test taking system when reading and preparing for our responses.

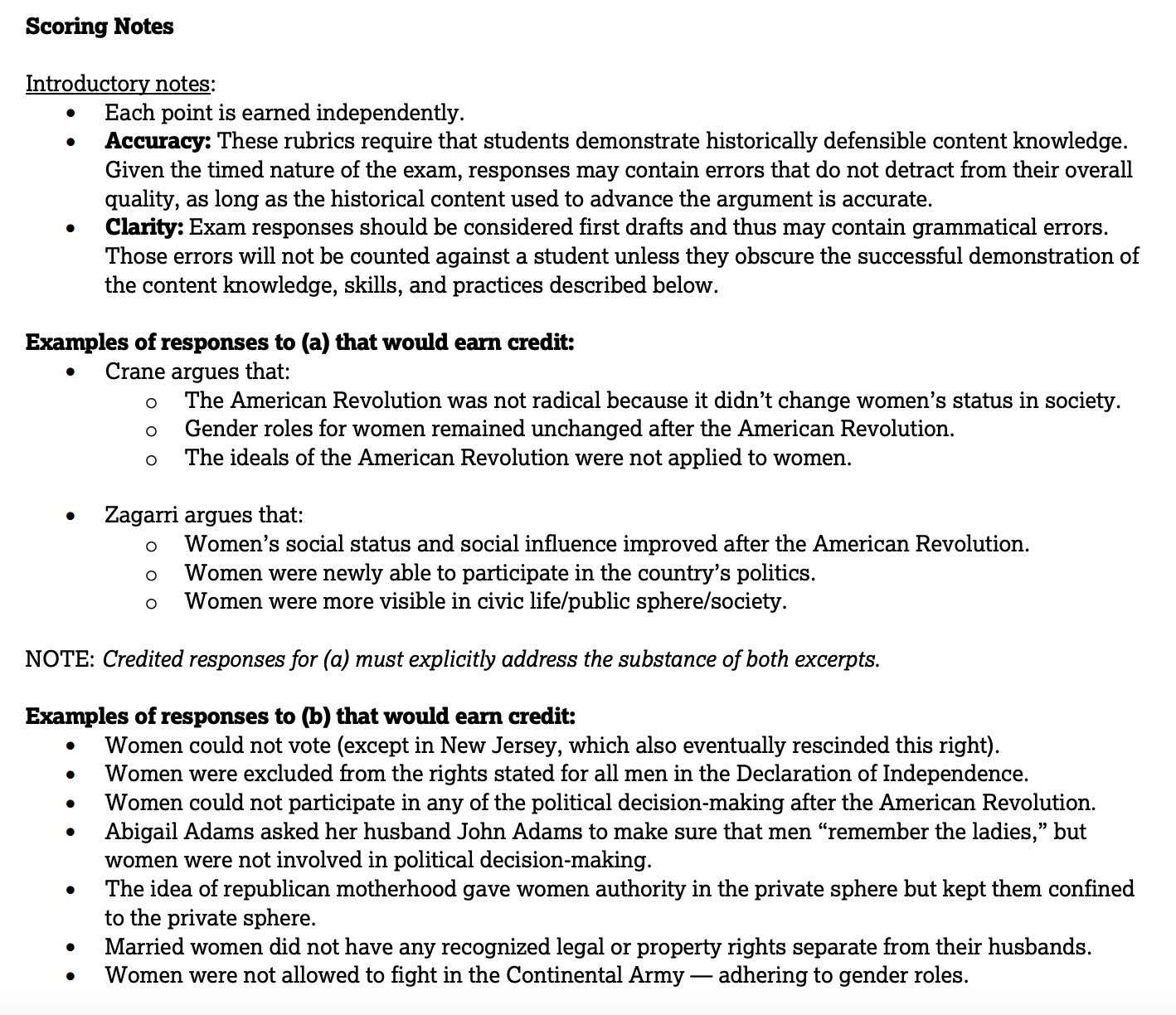

Source: College Board

As you can see in the above, the first SAQ of the 2019 AP® US History exam was assessing students' abilities to describe and explain. In the majority of SAQs, you'll be asked to describe or explain a response to stimuli.

For DBQs and LEQs, you'll be asked one of three essay types: compare, change and continuity over time, or causation. This is commonly phrased using the directive words, "evaluate the extent of…".

It's easy to circle or underline the key phrases that you're being asked to respond to.

There are two "key phrases" to commit to memory when it comes to AP® US History short answer questions:

- Describe

- Explain

That's it. If you review the last several years worth of released exams, these are the most commonly used directive words for the short answer question section of APUSH.

If you aren't sure what these words are asking you for, keep reading.

When the exam asks you to describe something, you need to tell them about what they're asking. This doesn't mean you need to explain the "why" — it just means you need to talk about what the topic is and the characteristics of the topic being asked.

When you're asked to explain something, this is where you need to show the "why". You need to be able to give 3-5 sentences with an example in most cases to earn credit for these questions.

After you've identified the key directive words, make sure you take note on how many examples you need to provide in your response. Sometimes students go above and beyond in their response, but what they don't realize is that if they give more than what was asked, the reader will move on after the student reaches what the question has asked (i.e. the question asks you to describe one thing and you state three; in this case, only the first is considered for your score).

One of our favorite test taking tips is to make a tick mark or star next to the words you've circled or underlined after you've answered it in your free response. This gives you a visual way to ensure you've answered all parts of the question.

It can be so easy to not answer the question that's being asked of you.

Aside from describe and explain, here are other potential directive words the College Board may give you for AP® US History:

- Compare : Talk about similarities and/or differences.

- Evaluate : Determine how important information or the quality/accuracy of a claim is.

- Identify : Give information about a specific topic, without elaboration or explanation.

- Support an argument : Give specific examples and explain how they support a thesis.

3. Plan your response BEFORE beginning to write your response.

When the College Board shared their favorite AP® US History exam tips , they put this at the very top of their considerations. They describe that it's common for students begin writing responses immediately and as a result, students create poorly planned responses that are disconnected.

Remember, the FRQ is intended to test your ability to connect the dots of what you've learned in class to historical thinking skills. The crucial skill is being able to identify evidence, and connect it to a historically defensible thesis as part of your historical analysis.

To do so elegantly, you must plan out your response before you begin writing.

Here's what we suggest: read the question once to circle the directive words. Then read it a second time to ensure your understanding of what's being asked. If needed, read the question a third time and think about how you'd word the question in your own words.

Craft a clear thesis statement. An easy way to do so is with the "although A, XYZ, therefore" model. We go over this in our tips section below. Ask yourself, is my thesis defensible? Can I agree or disagree with it?

Then, think about what evidence you can bring in to respond to the question — how does this evidence connect back to your thesis? Do not leave it to your reader to infer what you mean when you include certain supporting evidence.

This process will help you start to think through what you're actually answering and how you'll answer the "why" based questions. It'll also help you avoid simply restating the question without adding any direct response to the question (what is known as a historically defensible thesis or a thesis with a clear line of reasoning).

4. Remember that AP® US History DBQs and LEQs require you to demonstrate four key skills: formation of a thesis, contextualization, sourcing, and complexity. SAQs should directly respond to what's being asked.

For short answer questions in AP® US History, you do not need to write an essay to score all the possible points. There is no need for an introduction, thesis, or conclusion on these questions.

For the DBQ and LEQs, scoring is clearly outlined on a respective seven and six point scale.

For the DBQ, you need to be able to:

- State a defensible claim or thesis that responds to the prompt and establishes a clear line of reasoning.

- Contextualize your response in the broader historical context (for APUSH, it's typically demonstrating knowledge of the last 50-100 years prior to the time period asked in the prompt).

- Support your claim with a certain number of accurate and relevant evidence

- You earn one point for using content from at least three documents to address the prompt and two points for using six documents as well as supporting an argument in response to the prompt.

- You earn an additional point for bringing in at least one piece of outside specific historical evidence beyond what has been provided.

- For analysis, students must source at least three documents discussing the author's point of view, purpose, historical situation, and/or audience in relation to the thesis as well as illustrate a complex understanding of historical development to incorporate nuance into their response.

What this means is that as long as you cover all the points outlined above clearly, you can score a perfect score on the AP® US History DBQ.

For the LEQ, much is the same in the core rubric in terms of needing a thesis, providing contextualization, and analysis. For evidence, there is not a requirement for additional evidence beyond what is provided since that's the entire point of the evidence section in crafting a long answer question response.

When you're going through your mental checklist of whether you've demonstrated these skills, ask yourself if you've "closed the loop". This is a test taking strategy the College Board promotes across multiple disciplines and with good reason — it challenges a student to demonstrate they can form a coherent argument. Closing the loop in AP® US History can mean using words like "because" or "therefore" to help bridge two concepts together and solve for the "why" this matters.

5. Practice, practice, and then practice some more.

The nice thing about AP® free response sections is that they're generally pretty predictable to prepare for. Ultimately they come down to knowing how you're going to be assessed, and learning how to craft responses that match those criteria.

When you start preparing, try a set of released questions and then have your friend grade your responses with the scoring guidelines. See how you might have done without any intentional practice.

Then, review your mistakes, log them in your study journal and begin to tackle the areas where you're weakest. Typically students struggle most with the evidence and analysis sections of the APUSH exam.

After a few times of doing this, you'll have a stronger intuition towards the test and feel more confident heading into test day.

Return to the Table of Contents

37 AP® US History FRQ Tips to Scoring a 4 or 5

Now that we've gone over the 5-step process to writing good APUSH free responses, we can shift gears to tackle some test taking tips and tricks to maximizing your FRQ scores.

We recommend you review these several weeks, and then days before your exam to keep them top of mind.

15 AP® US History Short Answer Question Tips

- To tackle SAQs, remember the ACE acronym:

- Answer the question.

- Cite your supporting evidence.

- Explain how your evidence proves your point.

- Focus much of your prep time on the E in ACE . Students often are not effective at earning the point for explaining because they simply restate a fact and fail to show how that fact supports comparison, causation, or continuity and change over time.

- Practice demonstrating comprehension of historical excerpts by working on sharing ideas from different sources in your own words. Review both primary and secondary sources.

- Practice supporting your main points of your thesis, and then practice supporting your minor points and details.

- Be specific in your responses to questions. It is not enough to say for example that "something changed". What changed, how did it change and what might have prompted that change?

- One of the easiest ways to bridge two concepts is to use words like "because" or "therefore" and then proceed to answer the "why this matters". Always double check that your answer addresses the how and the why — this is a good gut check for whether or not you've been specific enough.

- To help you score points in demonstrating your historical reasoning skills, use words like whereas, in contrast to, or likewise when drawing comparisons.

- Think of short answer questions as pop quiz drills, rather than full essays. There is no need for having a thesis in each SAQ response.

- Stick to the right time period and review your chronology. Sometimes students bring in irrelevant information from outside the time period being asked in the SAQ. More recently this happened in 2019 where students brought in information about women's history that was not relevant to the time period asked.

- When presented with a stimulus such as an image to interpret, be sure that your reference to key concepts from class ties back to that stimulus. For example, "this image demonstrates the historical concept of CONCEPT, which was DEFINITION. This can be seen by the DESCRIPTION OF HOW THE IMAGE RELATES to the CONCEPT.".

- Review your geography of the colonies. Students have commonly confused middle colonies with New England colonies in recent years. When you review here, be sure to go over the specifics on what was happening in these colonies socially, economically, and politically.

- Pennsylvania and Maryland are not part of the New England colonies!

- Know your key definitions with specificity. For example, it's not enough to only state that the New Deal and Great Society programs helped the economy. To earn points, you must distinguish how the New Deal focused on America's economy after the Great Depression to combat unemployment while the Great Society focused on social supports via Medicare and Medicaid to support Americans.

- Review your wars and presidents before, during and after key wars. Students have often confused things between WWI and WWII or between the Korean and Vietnam wars.

- Do not use the outcomes of a government program to describe a difference. Just because one program for example was successful while another was not does not demonstrate that you've mastered the content knowledge.

- Don't extrapolate if you are not completely sure about something introduced in a primary source. Students typically do this accidentally when they say an extreme statement like "always" or "never" when describing something.

- For example, just because a primary source demonstrates something about a particular group of people doesn't mean it necessarily applies to that entire geographic region. There is often nuance, which is why we study history!

17 AP® US History Document Based Questions (DBQ) Tips

- In your thesis, make sure you don't just restate the prompt. You need to establish a clear line of reasoning. The easiest way to do this is to remember the model: Although X, ABC, therefore Y.

- X is your counterargument or counterpoint

- ABC are your strongest supporting points for your argument.

- And Y is your argument.

- If you don't like the above formula, another common way to form a thesis is to use the word "because" — the claims you make after you state "because" will be your argument.

- Cover your contextualization point in the introduction of your essay. The easiest way to do this is to discuss what was happening 50-100 years before your prompt and its relation to your thesis.

- Get comfortable grouping your documents into two or three categories — this typically helps demonstrate higher-level thinking. Think about for example putting all the documents related to political factors together, and economic factors in another group. Past responses that have not scored as highly often have sequential explanations of each document. For example:

- In document 1, XYZ

- In document 2, XYZ

- Etc.

- Be sure to have clear topic sentences that relate back to your thesis. This helps you avoid document listing without direction in your essay.

- It's not enough to just describe the content of the documents.You need to relate what's going on in the documents to your thesis. Students lose points here for failing to include clear arguments or claims in relation back to their thesis.

- The easiest way to earn the point for describing the documents and then applying the documents to support your thesis is to remember the word therefore .

- XYZ, therefore ABC

- XYZ is the description of the document

- ABC is the implication and support of how what you described relates to your thesis.

- Many students struggle with author purpose and point of view. Practice articulating what you believe to be the intention of the authors of documents and connecting it back to your argument. Don't just say "the author has this point of view".

- Know the sorts of statements you need to make when answering the different categories of essays:

- Continuity and Change Over Time: You should include at least one "however" statement at the end of every body paragraph. Example: XYZ changed…; however, one continuity was ABC…"

- Compare/Contrast : You should include a similarity and difference at the end of every body paragraph: "XYZ similarities…however, one difference was ABC…"

- Cause/Effect: Have at least one therefore statement at the end of each body paragraph. "XYZ happened….therefore, ABC consequence of XYZ happening"

- Sourcing is earned when specificity and significance is included in discussing historical context, audience, purpose, or point of view. You don't earn it by making general statements.

- When sourcing, you only need to use one of the skills for each document you source. Don't feel the need to go over historical context, audience, purpose, and point of view for every single document you are trying to earn sourcing for.

- Source at least four or five documents to be safe, in case you're wrong in one of your interpretations.

- Be sure to incorporate a few examples of historical evidence from each decade from beyond the documents you're given — this is worth a full point on your DBQ.

- When you incorporate outside evidence, make sure it's from the same period you're writing about. Chronology and time periods are important!

- Complexity is often earned by introducing a more sophisticated understanding of the prompt. This means for example qualifying an argument with a nuanced discussion instead of only addressing what was asked in the prompt.

- It's more than just including the word "however" to qualify an argument. It's considering the broader picture and implications.

- It can also be demonstrated in the form of illustrating contradictions between documents or historical events in relation to the thesis.

- The easiest way to earn complexity is to do the opposite of the historical reasoning skill you've been asked of. For example:

- If you're writing about change over time, discuss continuity of time.

- The College Board rubric describes this as "explaining relevant and insightful connections within and across periods"

- If you're writing about a comparison, talk about the contrast.

- The College Board describes this as "explaining both similarity and difference"

- If you're writing about causation, discuss the effects.

- If you want another way to earn this point, you can earn it by applying your argument to another time period and drawing a connection. If you do this, keep in mind you must apply your entire argument to another time period.

- If you're writing about change over time, discuss continuity of time.

- A few possible stems to signal to your grader you are attempting complexity is to say use one of the following phrases: another time, another view, or another way.

5 AP® US History Long Essay Questions (LEQ) Tips

- Your thesis does not need to just be limited to the model of addressing economic, social and political issues. Students have often overused this format when they could be better off understanding core AP® US History themes and how they relate to the question being asked.

- Make sure you know your time periods. Students often lose points when it comes to evidence because they bring in concepts that are outside the scope of the time period or region. Chronology is important across the entire AP® US History exam.

- Review the causes of key events and how the occurrence of key events impacted society over time. For example, what was fought for in women's rights before Roe v. Wade, what led to it happening, and what were the outcomes from the case happening going forward in relation to women's rights?

- Show the "why" of the evidence you're providing. It's not enough just to mention a concept. Explain to the reader why you are including that concept or evidence and relate it back to your thesis. Evidence should further your argument.

- If you're answering a continuity and change over time question, make sure you also discuss continuity. Students often only talk about change over time.

Return to the Table of Contents

Wrapping Things Up: How to Write AP® US History FRQs

Whoa! We've reviewed a ton of information in this AP® US History FRQ review guide. At this time, you should have an actionable 5-step plan for your FRQ prep as well a 37 test taking tips to prepare with.

Putting everything together, here are a few key things to remember:

- Students who excel on the AP® US History free response section do so because they understand how they're being graded. Master the rubrics. Understand how and when points are awarded and not rewarded. There are tons of previously released exams to help you here.

- Follow a regular system for responding to each question. Whether it's our approach of identifying the directive word, planning and then writing while checking off after you've answered each part of the prompt, have a methodology in the way you craft responses.

- Remember the ACE acronym for SAQs: answer the question, cite your evidence, and explain how your evidence proves your point.

- Focus your time on chronology, time periods and course themes. This will help you write within the scope of the time period given in each question and not lose points by mistakenly incorporating something outside of the time period being asked.

- Review commonly tested AP® US History topics. Review the curriculum and exam description to see the percentage breakdown of different units. Units 3 through 8 are always more important for the exam than Units 1-2, and 9.

- Make sure your thesis includes a clear line of reasoning. Remember the model: Although X, ABC, therefore Y.

- Always "close the loop". Use words such as "because" or "therefore" to bridge two concepts together and solve for the "why" this matters.

We hope you've found this FRQ guide helpful for your AP® US History exam review.

If you're looking for more free response questions or multiple choice questions, check out our website for more valuable exam prep! Albert has hundreds of original standards-aligned practice questions for you with detailed explanations to help you learn by doing.

If you found this post helpful, you may also like our AP® US History tips here or our AP® US History score calculator here.

We also have an AP® US History review guide here.

Source: https://www.albert.io/blog/ap-us-history-frq/

Post a Comment for "Continuity and Change Over Time Apush Jefferson and Jackson"